Players and commentators talk a lot about playing each ball on its merits, but actually it’s not always that good an idea. Ben Duckett and Zak Crawley gave an illustration why in the 2023 Ashes.

It’s a mad but completely true fact that England haven’t had a settled opening partnership since Andrew Strauss retired in 2012. Let’s quickly run-through who’s had a stab at opening since then (excluding the other half of that partnership, Alastair Cook).

In chronological order (deep breath)…

- Nick Compton

- Joe Root

- Mike Carberry

- Sam Robson

- Jonathan Trott

- Adam Lyth

- Moeen Ali

- Jos Buttler

- Alex Hales

- Ben Duckett

- Haseeb Hameed

- Keaton Jennings

- Mark Stoneman

- Rory Burns

- Jack Leach (twice)

- Joe Denly

- Jason Roy

- Dom Sibley

- Zak Crawley

- Ben Stokes

- Alex Lees

Three of those players averaged over 40: Joe Root, Jack Leach and, so far, Ben Duckett.

No-one else has averaged more than 31.33.

Only five others have averaged over 30: Nick Compton, Sam Robson, Rory Burns, Joe Denly and Zak Crawley.

The bar for being considered a viable England Test opener has dropped a touch.

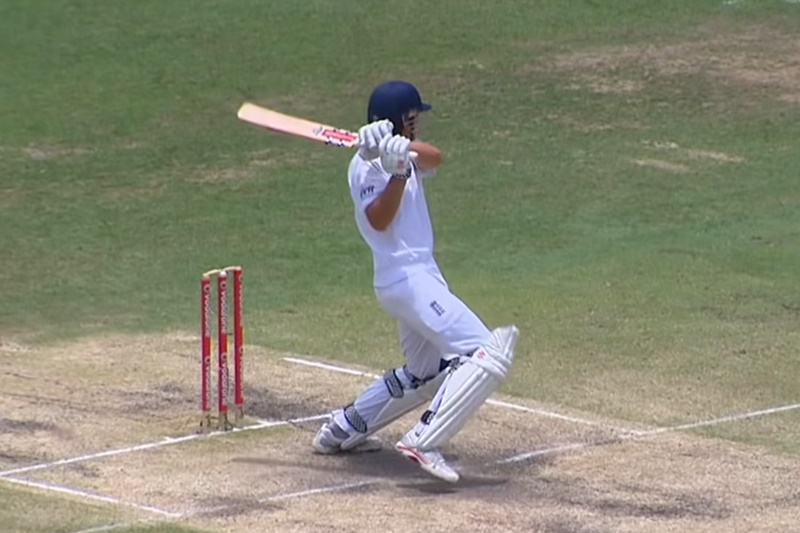

Cook lite

It has been a bit of a production line – one for some reason calibrated to churn out mediocre products. The sameyness of the records is striking. We’ve seen a lot of batters averaging mid- to late-20s and pretty much all of them boast strike-rates in the region of 35 to 45 runs per 100 balls.

The average innings has been characterised by studious watchfulness before either getting out to a pretty good ball or ‘giving it away’ after running out of restraint.

That’s of course a generalisation – we’re talking about hundreds of innings here – but those strike-rates don’t lie. Whether knowingly or not, a lot of people tried to imitate Alastair Cook and it is a mark of Cook’s freakish psyche that he proved wholly inimitable.

But there have always been other ways of going about things.

Cook and Strauss averaged 40.96 as an opening partnership, but that was actually a sizeable step down from Strauss’s partnership with Marcus Trescothick, which averaged 52.35, and Trescothick’s with Michael Vaughan, which averaged 48.76.

It was good to bat with Marcus Trescothick. Marcus Trescothick hit the ball.

Ben Duckett

Before the Ashes began, an incredible statistic was doing the rounds that Ben Duckett had left only eight of the 605 deliveries he’d faced as a Test match opener. According to Andy Zaltzman. Test openers ordinarily leave about a quarter of the balls they face.

When the series got underway, Duckett continued in a similar vein, playing at the first 100 deliveries he faced before leaving two of the 134 balls he faced when making 98 at Lord’s.

He wasn’t happy about this.

“One of them should have been a wide and the other one was probably over my head, so I was gutted,” he said.

Duckett is comfortable with his approach, in large part because he has been given the green light by his coach and captain.

“If I think back to maybe three years ago, I was thinking that I could never be an opener in Test cricket because of how I play, and then actually last summer I was like, ‘why not?’” he told the Independent. “Why do I have to bat like Sir Alastair Cook or these great openers of the past?”

Why indeed? It’s not like it was working for anyone else. Other than the occasional, not-very-serious flirtation with an alternate approach, England spent literally years frustrated with square pegs for not going through round holes without ever seriously considering the hole’s part in this interaction.

More shots

One very obvious reason why the flirtations referenced in the previous paragraph never came to much is because playing more shots tends to mean playing more bad shots and if there’s one thing you can count on in this day and age, it’s that the bad shots of a losing side will take on colossal significance.

Why did the team lose? Why are they so terrible? Cue a montage of all the bad shots.

We’re as guilty of this as anyone, but in our defence, we don’t do it to be critical. We do it because it’s funny and maybe also as a bit of a coping mechanism.

Ben Stokes and Brendon McCullum have brought about basic everyday competence with the bat because they don’t care about bad shots. We’ve already written a whole thing about this and we don’t want to reproduce great tracts of it here. The jus of it is that they see the bigger picture, which is that a batter who sometimes plays the wrong shot is nowhere near as bad as a batter who’s always worrying about playing the wrong shot.

And do you know what’s also true? Playing more shots probably means playing more good shots too and this brings benefits that extend beyond the mere runs you score.

Proactive batting

Before Cook and Strauss and before even Trescothick and Vaughan there was another England opening partnership that warrants a mention. Between 1990 and 1995, Graham Gooch and Mike Atherton averaged 56.84.

Those who only remember late-era Athers or only know him by reputation won’t really appreciate what he was like in his early-20s before back-knack began to diminish him. This was the best of Atherton – a period in which he averaged 45 and scampered frequent singles with age-defying fitness freak Gooch.

Because that was what their partnership was built on really: not leaves, but singles.

It was far from the helter-skelter scoring-rates we’re seeing right now, but at the start of an innings, when catchers were in position, Gooch and Atherton worked the gaps. They worked the gaps until they were filled, at which point the risk of dismissal reduced.

That is proactive batting.

In 2013, we described Kevin Pietersen as the only upper order England batter prone to trying to set his own field. All the others at that time played according to what they were presented with. A good few people misread this as a call for more six-hitting and reverse sweeping. That wasn’t at all what we meant, so we tried to clarify.

Our gripe was that while playing the ball on its merits is almost universally regarded to be ‘a good thing,’ that kind of passive, reactive batting can leave the player pretty much helpless against the best bowling. If every ball merits either a leave or an honest, respectful defensive stroke, you don’t go anywhere, you stagnate, and eventually you get out.

Graham Thorpe was the player we eventually alighted on as a less emotionally loaded example of a proactive batter. Like Pietersen, or Atherton with Gooch, Thorpe would actively seek out scoring areas and exploit them in a bid to force the fielding captain’s hand. Hard-running was a big part of this (although boundaries are always more persuasive).

Pretty persuasion

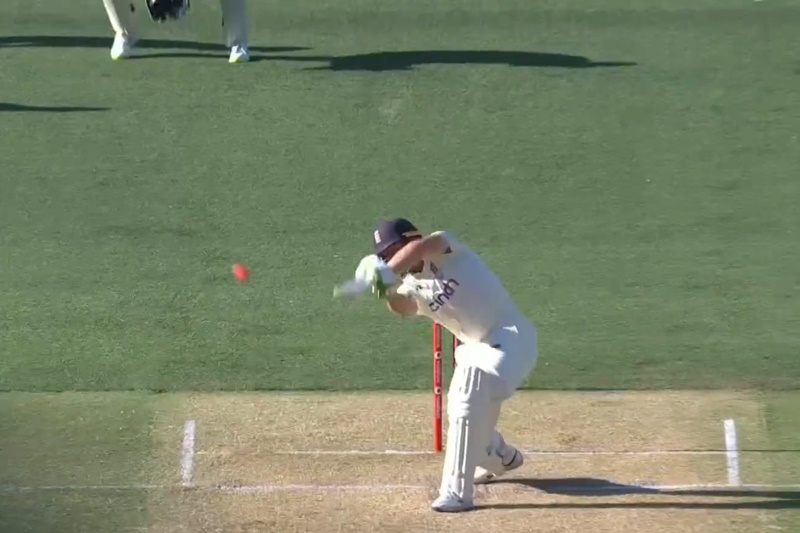

England have an almost entirely proactive batting line-up these days. There are plenty of unignorable manifestations of this, but a few subtler ones too, such as the tendency to advance down the pitch to quicker bowlers that Jarrod Kimber has written and done a video about.

The openers start as everyone else means to go on.

The early parts of Zak Crawley’s 189 at Old Trafford brought a good few reminders that he is the most gifted inside-edger in world cricket, but his and Duckett’s inclination to lay bat on ball undeniably has an impact.

Bowlers always feel in with a chance against them, but with their opposite-handedness and a difference of 25cm in height, they’re a bloody nightmare for settling on a line and length. Singles often ensue. Throw in the fact that both of them will definitely – definitely – try and smash every bad ball to the boundary and it can be hard to retain an attacking field for long.

Crucially, there are growing signs that the two of them are content to adapt to these resultant field settings rather than being seduced by their own boundary hitting. This is actually when they start looking good.

After eight fours in the first five overs of their second innings at the Oval, Duckett and Crawley nurdled. It didn’t last that long – only 10 overs or so – but nurdling can be positively murderous when the bad balls are also being put away. With men on the boundary and few catchers, England’s openers were cruising – yet the alternative for Australia felt worse.

This is the point at which you can start playing the ball on its merits – once you’ve earned it.

About this article

These longer features are only possible thanks to our Patreon campaign and the dozens of magnificent people who contribute to it each month. We simply wouldn’t be able to carve out enough time to do these longer articles without that funding. If you like the site and enjoy the features, please at least have a think about contributing for a little while. Piffling amounts are more than welcome and you can cancel any time and we won’t hold it against you.

If you’re new to the site, ignore the paragraph above and just sign up for the email (which is free).

Do you remember pinch hitting? I know it was an ODI thing, but the idea was that you put your most agricultural batter in first and let him have an almighty warrung at everything. Muralitharan was the archetype. The plan was that by the time everyone realized that it was a bad idea, you’d have 70 quick runs and would be well on your way to winning. And if your pinch hitter was out for three, well so what – he was only due to come in at eight in any case.

To me, batting without reference to the delivery is just this. It was, I suppose, the forerunner of T20 batting – predetermine your shot (by picking a stand to put the ball in), and essentially try to hit whatever was thrown at you in that way. But what England are doing is different to this. It is still playing each ball on its merits, but just having a different (and better) mental map of what those merits are.

Much of this difference is how batters treat the new ball. In the olden days (two years ago), the key for the openers was “surviving the new ball”. After ten overs be 18 for 0. After another ten, be 50 for 0. And at lunch, be 90 for 1. Shine gone, opening bowlers being rested, slips reduced to two, and an incoming batter who has a bit more oomph about him. To achieve this, the key was leaving everything that “didn’t need to be hit”. They weren’t playing each ball on its merits, they were simply leaving everything that wouldn’t hit the stumps.

What’s changed is that all the batters, from one to eleven, has licence to dispatch every hittable ball. The increase in risk is minimal. This isn’t pinch hitting, it is just having a different set of criteria for analysing each delivery. Good balls are still defended, massively wide ones are still left, but those eminently hittable ones on sixth stump are hitted, eminently. New ball or not, the batters trust their ability to hit pretty much everything that isn’t either a wide or a jaffa.

I was at a minor function at Bowden CC a few years ago. In the main room, Graham Gooch was the guest speaker at a sportsmen’s dinner. As I walked past, I heard him describing to his audience the correct foot movement for leaving deliveries outside off. The implication was that with a straight back-lift the ball could be safely left, or if it cut back in defended with the full face of the bat. Very sensible. But in fact, entirely predetermined. The decision to play a defensive shot or leave had been made before the bowler started his run-up. In fact, I suspect it had been made about a decade or so earlier than that. No matter how bad the ball, the farthest it was going was into the keeper’s gloves.

I assume that after this, Gooch moved on to that time he drank Beefy under the table, or some story about a vicar finding himself in the women’s changing rooms. That’s how all the sportsmen’s dinners I’ve been to have gone. More likely though is that he moved onto hip positions for clipping one off the pads. If they hadn’t all been members of Bowden CC, I would have felt very sorry for them.

You have to wonder how quickly a new ball becomes an old ball through being relentlessly left as well. Look at Keanu Reeves versus Nigel Farage – not everything ages at the same rate.

Being smacked about a bit and having to spend more time in the party stand at Old Trafford has got to be pretty ageing.

How many sportsmen’s dinners have you been to with the audience regaled by the Gooches of this world? Good God, is everyone here Ged?

‘I’m Ged, and so is my wife’

Brian Moore was the latest one, at my rugby club’s centenary dinner. His best line was, “Since I started doing these things, one thing has changed enormously, and that is the presence of women players at what used to be known as sportsMEN’s dinners. I’m sure I speak for all the men here when I say that this is definitely something we can’t do anything about.”

Excellent piece.

Times change. Styles change. Not always for the better, but this change of test match batting style and mindset is most certainly a change for the better.

An aspect you don’t mention is the impact that T20 cricket has had on batting styles and the mentality of batsmen. Firstly, attacking batsmen (including those who like to open) are more common. Secondly, all top class batsmen now learn from experience that certain shots that come naturally to them are lower risk than people previously thought. Thirdly, most top class batsmen practice attacking and funky shots a lot, so they are better at them.

Geoffrey Boycott would not have done well trying to reverse ramp the first ball after lunch, but that’s mostly because he probably never attempted that shot in his whole life. Geoffrey would no doubt say that he didn’t have the talent to play such shots, but my guess is that he did have sufficient talent but he never had an environment within which to fulfil it.

Excellent piece, I say again, KC. Thanks.

Which Geoffrey are we talking about here? In one of his many autobiographies, GB picked himself into his greatest ever World XI, as an opener. I’m not suggesting he is necessarily wrong (he is though), just that he doesn’t suffer excessively from self-doubt.

We’re pretty sure he once bought Jonathan Agnew ‘Boycott: The Autobiography’ as a birthday present.

This is a bit of a lame gag if done knowingly, but incredibly funny if done earnestly.

Equally self-effacing pundit Fred Trueman did not pick himself into a greatest ever team. However, he did say that the greatest ever fast bowler was Brian Statham. Since absolutely nobody would put Statham ahead of Trueman on the list, this was a far more subtle way of doing exactly the same thing.

Trueman once had to go to hospital after being hit on the box in a match. The box, made of bakelite, shattered, and shards of plastic had to be carefully removed from Fred’s scrotum. You can read all about it in his autobiography, Ball of Fire.

In the early days of T20, when test cricket was still on free to air TV, I recall Mark Nicholas interviewing Boycott, including a discussion about the “attacking from the word go” style of opening.

Boycott suggested that he wouldn’t have had the ability to bat that way. Nicholas suggested that Boycott probably could have done well playing that way, had he trained from the outset to play that way. Faux modesty it might have been, but I do recall him saying it…

…on free-to-air TV…not at one of those pompous cricket dinners/talks that I (and Daisy) mostly eschew. Mercifully we don’t move in the sort of corporate circles within which attendance at such events is virtually a requirement.

I am taking a bit of issue with the positioning of this article (not the message or content)

Sehwag always claimed he played each & every ball by its merit. & having watched his various test innings I can confirm it is 100% true.

It is the KP like scatter the field strategy

When the field is in, then the gaps are outside & he plays the lofted shots. What happens next is most crucial. When the field gets spread out, he is very content to pick the singles on offer. Not the stereotypical Sehwag we know.

I mean to say that in attitude & approach Sehwag is 100% a proper test batsman.

It is only his technique/skills that let him down, especially in English conditions

Yeah, the article is as much about assessments of each ball’s merits and recognition that there is in fact much to be gained from erring on the side of hitting the thing.

Sometimes our headlines are more about getting people through the door than 100% accurate synopses of what’s being said in the body of the article. This one’s a bit disingenuous.

The final line is really our way of saying that once you’ve reduced risk, you don’t necessarily need to go and seek it out.

I have a theory: the ball’s not just the ball, if you see what I mean. You probably don’t. Bear with.

When people say they are “playing the ball on its merits” they don’t just mean the physical object – how shiny or hard or polished it is. They’re definitely referring to the possible trajectory of the ball, its line, length, pace, how much it’s been moving or bouncing or turning and so on. But also if you play the ball straight into the hands of a fielder placed for exactly that shot, then say “the ball was the perfect trajectory to hit to that position”, nobody would say “that’s okay, it just proves you played the ball on its merits”. So definitely the field placement also counts as part of “the ball” and its “merits”. This may even extend to which fielder is positioned where, once you get to the stage of which ones are worth trying a quick single to.

I think this proves “the ball” has always gone beyond “the ball”, to include certain situational elements. A proactive strategist would realise that manipulating the ball into particular areas gives you a degree of extra control over that situation by letting you manipulate the field placement, or at least putting the fielding captain under pressure to react to retain control. A new ball that has the potential to be given a good thwacking is also a ball that is going to start feeling decidedly less “new” in the near future. Perhaps these features were not classically considered to be part of “the ball” and “its merits” but it’s just an extension of things that were accepted before, and if it’s serving a good purpose then why not?

I suppose the problem is where do you stop, before “just playing the ball on its own merits” involves a massively complex matrix of overcomplicating factors and the batter is too bogged down to think clearly and quickly. But the Bazballers don’t seem overburdened by such things – it seems more like a realignment to seeing the merits of a typical ball as more likely to involve being dispatched, or at least struck, than had previously widely been believed. There are some things that don’t count as part of “the ball” – presumably the match situation (you might want batters to adapt in tone, more aggressive or more defensive, based on whether quick runs would be very valuable right now for example, but that doesn’t count as “the ball”) and certainly batters thinking about career preservation when considering how they play the ball are not really playing “the ball” (which is why management backing their selection choices rather than threatening to wield the axe on them is so useful).

I think ‘the ball’ in this context is the unit of play (ie one-sixth of an over). So the context (including the field placement, the game situation, the overhead conditions, whether the bowler has bowled 10 overs straight without a break, whether you have just insinuated something about the wicketkeeper’s family history, the absence or presence of a bestial roar in response to the previous delivery, etc) is included.

It’s the short-term version of playing one game at a time, taking it day by day, etc.

In order for anyone to play any ball at all it needs to stop raining.

#justsaying

#allthisrainisjustsoirritating

I notice the Bledisloe Cup – in a sport which cannot be disrupted by rain and it can often enhance proceedings – was played under a roof.

What a bunch of wimps, those antipodeans.

Here in the real world, Daisy and I took great pleasure in watching the second half of the netball this morning, after which Daisy has been watching “Hitler Channel” documentaries while I have finally got around to sorting out my backups. That sort of day.

I always suspected. We all did.

The netball, you mean, Sam?