We do enjoy limited overs games, because variety is one of cricket’s greatest strengths. However, the action’s all limited to one end of the cricket spectrum, so it offers less variety when ‘consumed’ in isolation. Test cricket has greater scope – a wider range of possibilities – and so that’s what we miss about it when the format’s not being played.

A lot of guff gets spouted about traditions and tangentia when talking up Test cricket, but we try not to confuse all of the surface-level features and rituals we associate with the format with what truly endears it to us.

Here are some of the things we miss at times like this.

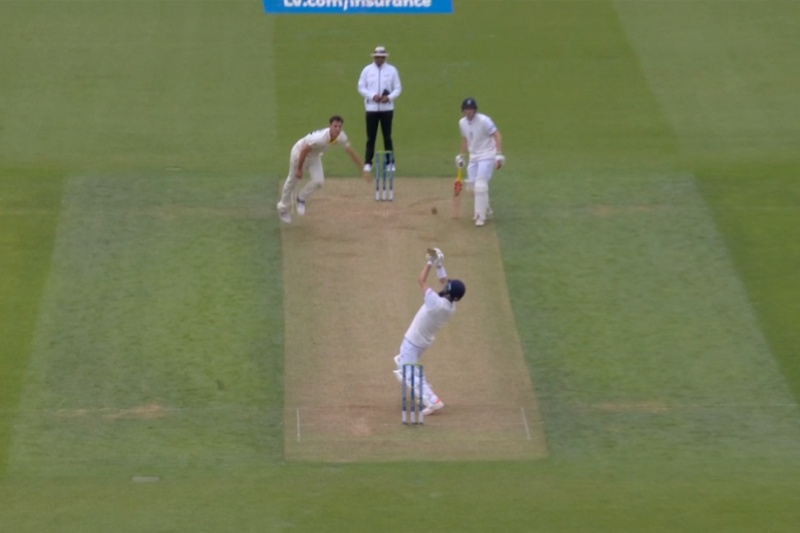

1. Batters choosing to play wild shots

The shorter formats aren’t short of weird and wild shotmaking. We’re meant to marvel at the audacity of the batters – and often we do – but there’s a key detail that takes the edge off for us. When a team’s innings lasts only 100 or 120 balls, there is every incentive to be ambitious when trying to reach the boundary rope.

In Test cricket, it’s different. Time is far less of a constraint so batters can choose how they go about things. For us this means that when Joe Root ramps the ball for six first ball or when Moeen Ali tips one off his nose for six, it’s massively more exciting.

It’s only brave when you have options.

2. Endless batting

There is a trend among stubborn traditionalists to champion styles of play that you don’t really see in T20 or the Hundred. A certain sort of person delights in celebrating batters digging in or attritional sessions that are generally billed as being “for the purists” afterwards.

These are of course important and sometimes intriguing elements of the longer format, but to embrace them to the exclusion of all else seems to miss a far more straightforward benefit of Test cricket… which is that there’s more of it.

That’s of course great from an “I’m enjoying this and I can carry on watching it” perspective, but it also introduces a particular dynamic that you don’t get in white ball cricket. This is when the fielding side has completely and utterly lost control and just has to keep on bowling anyway. No time limits; no constraints; just an inescapably awful situation you have to either endure or find some way to change.

It is absolutely horrendous to be on the receiving end of an 18-ball fifty; or to spiral down the plughole as an opposition batter races to reach three figures before they run out of overs; but it is massively more unsettling to bowl at Zak Crawley when he’s on 150 off 152 balls and he has every intention of just carrying on exactly as he has been doing, while Harry Brook, Ben Stokes and Jonny Bairstow are still itching to get started.

That’s a true horror scenario – one without a finish line.

3. Endless bowling

Endless batting also means endless bowling. This is fascinating when runs are flowing and there’s no place to hide, but it’s just as significant a feature of Test cricket that sometimes it is the batters who would very much like what is currently happening to ideally not be happening.

Mark Wood’s first spell in the 2023 Ashes was four overs long, so technically it could have fitted into a T20 game. The field might have been a bit different and it’s unlikely he’d have bowled all four overs on the reel, but it’s not impossible that something akin to that electrifying passage of play could have taken place in the shorter format. The thing is, that wasn’t the end of Mark Wood for Australia in that innings. He got through another 7.4 overs after that and then bowled another 17 in the second innings. As a spectator, each time Wood came back felt like a really big and exciting deal.

Admittedly, fast bowlers remaining fresh enough to actually bowl quickly is one of the great things about 20-over games, but it’s also very frustrating when someone’s clearly on a really, really good day and they’re barred from continuing because they’ve already bowled 20 or 24 balls. It feels like tapas when you’re in the market for a feast. Give us more! Why are you holding out on us?

We’ve been referring to fast bowlers, but it’s actually even more of a frustration when use of a bowler doesn’t especially diminish them. Think of Murali at the Oval in 98.

That’s when a bowler’s most terrifying for the opposition: when he’s staying put.

4. Overnight

Overnight is such an important part of a five-day Test match. You of course get plenty of opportunities to take stock and evaluate during a league competition, but it’s not quite the same thing. During the Hundred or the IPL, you’re fundamentally watching different iterations of the same thing, whereas stumps during a Test match brings an opportunity to weigh a thing that is still evolving.

5. Players who can’t bat having to bat

We like tail-enders batting and tail-enders pretty much always have to bat in Test cricket. Even if they do get to the crease in a limited overs match, they probably won’t be around for long.

This is a shame because it is endlessly fascinating watching someone who is pretty crap at a given thing being forced to do that thing against elite athletes with a top level match at stake. This makes it doubly incredible when they succeed, like when Pat Cummins played a blinder in the first Ashes Test earlier this summer or when Jack Leach made one not out that time.

There’s a lot more jeopardy and therefore a lot more excitement when the outcome of a game rests in the hands of those least qualified to do the job. Test cricket’s habit of throwing people of limited ability into elite sport scenarios is a large part of the reason why it is the greatest sport of all.

This piece – and all our other features – are only possible thanks to our Patreon backers. If you’re not currently a King Cricket patron and you’d like to see us to do more with the site, you can help crowdfund us from £1 a month. You can find a longer explanation of why we do this and what you get here. Thanks for reading either way though. Maybe just sign up for the email if you kind of want to show support for us but don’t want to spend any money.

Actually the advent of top-grade, short-form cricket has mostly enhanced rather than diminished my love for test cricket.

Enhanced, partly because the skills that cricketers develop for short-form cricket are also wonderful to see in the long form game. In particular, audacious shot-making, variation bowling and ultra-high-quality fielding were far less common in test cricket 20 years ago (pre T20) than today.

Enhanced also because I enjoy the contrast between short form and test cricket, which is far more interesting to me than the contrast between test cricket and ODI cricket.

It just seems a shame this season that the test cricket was all done before the end of July, leaving almost half of the summer (and from the point of view of youngsters, most of the school holidays) test free. I hope that this style of scheduling – allegedly a one-off because of pandemic-induced rescheduling of world cup tournaments etc. etc. – really is a one-off.

Totally agree about the contrast. T20 and Tests are much happier bedfellows than Tests and ODIs because they accentuate each other’s strengths.

Not sure about the ultra-high-quality fielding in tests. It’s a shame to see a pace bowler mess up his shoulder trying to have a couple of runs at the boundary in a test match, like Mark Wood v India in 2021.

While on the topic of Mark Wood, his first innings at the Headingly 2023 test has to be one of my favourite non-batter batting performances in recent times. Nowhere near as ridiculous as Bumrah v Broad 2022, but great in its own way.